Registration for the Interfaces event is now active on the conference webpages.

ALL WELCOME!

To register, please visit the College of Humanities webpages:

http://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/research/conferences/interfaces/

Conference fee (includes buffet lunch and tea and coffee throughout the day ): £15

Please direct all enquires to Lisa (lrs204@ex.ac.uk) and/or Jennifer (jab228@ex.ac.uk)

This blog supports the forthcoming AHRC supported Research Workshop event 'Interfaces: encounters beyond the stage/screen/page', to be hosted at the University of Exeter on Saturday the 29th of January 2011. This event is part of the AHRC Beyond Text scheme.

Thursday, 28 October 2010

Friday, 6 August 2010

Beyond Text: short research pieces, example 3

'Lolita –Star as intertextual symbol'

Stephen C. Kenyon, Glyndwr University

The opening sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1967) ushers in evocations of Classical Hollywood, a smoothly flowing rhythm of fascination and seduction, disembodied forms caressing and permitting to be caressed, beckoning in a stylistic counterpoint of obsession, fetish and containment.

What follows, is Quilty: An ephemeral, implacable object, as disembodied as the severed personas of the opening sequence. Quilty, as Sellers, as Spartacus, and back again, a textual interface and intertextual star persona;

These first utterances would seem to provoke an initial sense of intertextual familiarity and reassurance for the viewer. Yet this image, of a drunken ghost manifesting from underneath a burial shroud, simultaneously places Kubrick’s previous film (Spartacus) to the forefront of consciousness and extricates it via the ridiculous nature of its arrival. The sheet wearing decadent operates as a visual throwback to a work that was, on a production and artistic level, an unsatisfactory exploration for the director. The character as image is operating as an intertextual inversion of itself, undermining the value of previous expression.

The return of serve is not answered by a corresponding rally, at least not by Quilty, this is a game played by Sellers as Star performer; the robed jester, the backwoods banjo playing letter reader, the boxer, the pianist, and finally, behind a bullet ridden painting the chameleon meets his demise, transferring wholly to image, to artefact.

A Kubruckian muse interlinking the star laden, top-heavy Kirk Douglas extravaganza of Spartacus, the reeling and chaotic opening sequences of Lolita, and projecting ahead to the multi-faceted black comedy performance of Dr Strangelove (1964), Sellers’ fractured, kaleidoscopic performance operates not simply as a “twofold nymphet”, but as a cohesive triumvirate meta-textual device between the three films.

Text by Stephen C. Kenyon, Senior Lecturer in Screen Studies, Glyndwr University, August 2010.

Stephen C. Kenyon, Glyndwr University

“What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet...”

The opening sequence of Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1967) ushers in evocations of Classical Hollywood, a smoothly flowing rhythm of fascination and seduction, disembodied forms caressing and permitting to be caressed, beckoning in a stylistic counterpoint of obsession, fetish and containment.

What follows, is Quilty: An ephemeral, implacable object, as disembodied as the severed personas of the opening sequence. Quilty, as Sellers, as Spartacus, and back again, a textual interface and intertextual star persona;

“...I’m Spartacus. Have you come to free the slaves or something?”

These first utterances would seem to provoke an initial sense of intertextual familiarity and reassurance for the viewer. Yet this image, of a drunken ghost manifesting from underneath a burial shroud, simultaneously places Kubrick’s previous film (Spartacus) to the forefront of consciousness and extricates it via the ridiculous nature of its arrival. The sheet wearing decadent operates as a visual throwback to a work that was, on a production and artistic level, an unsatisfactory exploration for the director. The character as image is operating as an intertextual inversion of itself, undermining the value of previous expression.

“Roman ping, you’re supposed to say roman pong.”

The return of serve is not answered by a corresponding rally, at least not by Quilty, this is a game played by Sellers as Star performer; the robed jester, the backwoods banjo playing letter reader, the boxer, the pianist, and finally, behind a bullet ridden painting the chameleon meets his demise, transferring wholly to image, to artefact.

A Kubruckian muse interlinking the star laden, top-heavy Kirk Douglas extravaganza of Spartacus, the reeling and chaotic opening sequences of Lolita, and projecting ahead to the multi-faceted black comedy performance of Dr Strangelove (1964), Sellers’ fractured, kaleidoscopic performance operates not simply as a “twofold nymphet”, but as a cohesive triumvirate meta-textual device between the three films.

Text by Stephen C. Kenyon, Senior Lecturer in Screen Studies, Glyndwr University, August 2010.

Labels:

case study,

film clip,

intertextuality,

Kubrick,

research piece 3

Thursday, 5 August 2010

Beyond Text: short research pieces, example 2

Case Study: Beyond Text encounters at the Movieum London Film Museum

New to the London Film Museum for 2010 is an exhibition celebrating the work of stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, entitled “Myths & Legends”. The exhibit--which displays a huge variety of miniatures, prototypes, and models from classic special effects movies such as Clash of the Titans and Jason and the Argonauts—constitutes an illuminating addition to a museum which focuses strongly upon ‘beyond text’ materials in the preservation and interpretation of cinema history and its impact upon popular culture.

The museum presents several distinct collections of materials, each crafted in distinct ways around approaches to cinema as cultural practice, industrial history, social history, creative industry and national identity.

My intention here is to touch briefly upon a few of the museum highlights as examples of interpretative beyond text practices which engage notions of mediation and memory at the interface between critical analysis, archival preservation and public consumption

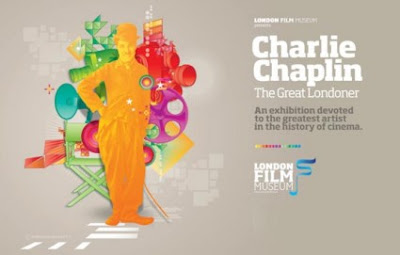

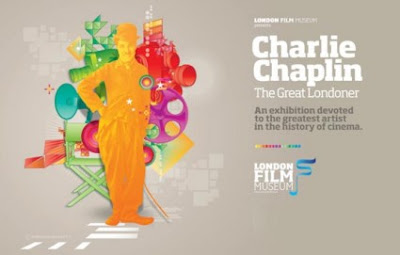

1. Chaplin Exhibition: the interactive map and the local reclamation of a global icon

The film museum features an extensive exhibit dedicated solely to charting the career and personal life of global comedy superstar Charlie Chaplin. What is interesting in the museum’s presentation of Chaplin is its attempts reclaim Chaplin as an explicitly national –and further a local cultural icon.

By offsetting a vast collection of ephemera surrounding and constructing his star image across a huge span of film history against a highly detailed account of his pre-cinema personal life and early career in Britain, the museum is careful to assert that Chaplin’s work and life outside of England is as an ‘exhile’.

One particular non-textual example from the exhibition illustrates this. The interactive map display is a wall panel with a street map view of a section of south London featuring a series of small red LED’s. These are able to be lit up by the museum visitor by pressing buttons beside a list of headings, which explain the plotting of each light as a site significant within Chaplin’s early life.

The detailed attention to incidents in Chaplin’s family life which precede his birth—the birthplace of his parents, for example—and minor incidents in his very early childhood—early homes, places of work etc within a small section of south London facilitate a compression of cinema history onto local historiography.

Chaplin is afforded the kind of geographical memorial frequently assigned to literary stars. The plotting of the coordinates of significant sites within his London life echoes the English Heritage plaques across the UK, which mark places of significance relating to influential figures from national history (such a plaque has been erected in Chaplin’s memory on the outer wall of his childhood home in Methely Street, Kennington).

The map’s function within the exhibit as a whole can be seen as a way of nationalizing Chaplin and reclaiming his silent screen Tramp persona from American cinema history. While later sections of the gallery space give way to charting Chaplin’s dominance of Hollywood (see, for example, the Chaplin-on-set display with the prominent ‘Hollywood’ sign featured in the background), the map attempts to ground the star within the familiar and the local, making Chaplin a British star rather than a Hollywood star, and specifically a London star.

2. Art Dept. Living exhibition / performed archive

A small amount of gallery space is given over to the ‘Art Department’—a space of semi-exhibition in which film artifacts are displayed alongside a handful of working artists, who are present daily sketching and designing at story-boarding stations.

The display of the living production of film projects offers the museum visitor a glimpse into the strange duality of a process which both produces future film texts and creates as a byproduct of this production ephemeral artifacts which, depending on the success and cultural impact of their overarching film project, will potentially become archived objects worthy of entering the surrounding displays within the museum.

At the same time, the staged nature of the ‘exhibit’ implies a notion of the archive as performance. Here we witness an archive being continuously created as a spectatorial process. The performed activities of the creative film worker become an archived event in of itself.

The power to ultimately reclaim the byproducts of this kind of production—the sketches, drafts, plans and cast-offs that the workers are here creating in a continual flow—lies with the museum viewer as potential audience member. Their decision to consume the end product—the film—determines the validity of its creative by-products as cultural history. If the film these storyboarders are currently working on flops, their sketches will be archived as personal professional history; if the film makes a substantial cultural impact, measured by box office success, such materials will become ‘validated’ ephemeral cultural history…

3. Myths & Legends, Ray Harryhausen: elevating the animator to auteur

The Harryhausen exhibition takes the thrills and spills of classic blockbuster cinema and frames them with the reverence of the ‘official’ museum. Lowbrow film fodder is broken down into the sum of its creative parts in order to locate an auteur within a disparate group of action-adventure films.

By locating Harryhausen as the central artists upon which the success and validity of such film hinges, the exhibit discards narrative sophistication and critical validation in favour of endorsing the oeuvre of the special effects artist.

Models of monsters, sword wielding skeletons and snake-haired medusas are mounted, lit and encased within sleek glass display boxes.

A miniature of Harryhausen’s memorable medusa stop-motion model is mounted in a dimly lit room, beside a huge screen projecting the Medusa scene from the original Clash of the Titans on a loop. Museum visitors enter this room in a reverential silence enforced by the darkness and glorifying single point of light illuminating the tiny stop-motion model.

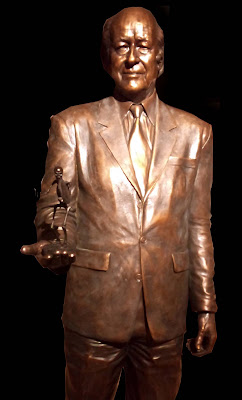

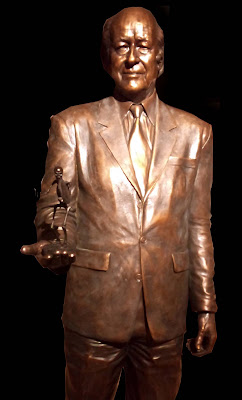

In the following room, Harryhausen is rendered in a life-size bronze statue, depicted as the powerful creator of movie magic holding a miniature skeleton from Jason and the Argenauts in his outstretched hand.

The display seeks ultimately to elevate Harryhausen’s work to auteur status in this way, further underscoring his significance by situating his work within a plotted history of stop-motion rooted in the pre-cinematic experimentation of Eadweard Muybridge.

Combining a reputable lineage of scientific advancement in visual experimentation with the trappings of the ‘official’ museum display and the prestige of cultural heritage this lends, the exhibition elevates the profile of Harryhausen’s work by divorcing his ‘artistry’ from its containing ‘entertainment’ textual forms. The Medusa creation in particular is thereby free to be celebrated as a technical achievement—one which surpasses the lowbrow connotations of the film in which it features.

Text by Lisa Stead, PhD Candidate, Dept. of English, University of Exeter

New to the London Film Museum for 2010 is an exhibition celebrating the work of stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, entitled “Myths & Legends”. The exhibit--which displays a huge variety of miniatures, prototypes, and models from classic special effects movies such as Clash of the Titans and Jason and the Argonauts—constitutes an illuminating addition to a museum which focuses strongly upon ‘beyond text’ materials in the preservation and interpretation of cinema history and its impact upon popular culture.

The museum presents several distinct collections of materials, each crafted in distinct ways around approaches to cinema as cultural practice, industrial history, social history, creative industry and national identity.

My intention here is to touch briefly upon a few of the museum highlights as examples of interpretative beyond text practices which engage notions of mediation and memory at the interface between critical analysis, archival preservation and public consumption

1. Chaplin Exhibition: the interactive map and the local reclamation of a global icon

The film museum features an extensive exhibit dedicated solely to charting the career and personal life of global comedy superstar Charlie Chaplin. What is interesting in the museum’s presentation of Chaplin is its attempts reclaim Chaplin as an explicitly national –and further a local cultural icon.

By offsetting a vast collection of ephemera surrounding and constructing his star image across a huge span of film history against a highly detailed account of his pre-cinema personal life and early career in Britain, the museum is careful to assert that Chaplin’s work and life outside of England is as an ‘exhile’.

One particular non-textual example from the exhibition illustrates this. The interactive map display is a wall panel with a street map view of a section of south London featuring a series of small red LED’s. These are able to be lit up by the museum visitor by pressing buttons beside a list of headings, which explain the plotting of each light as a site significant within Chaplin’s early life.

The detailed attention to incidents in Chaplin’s family life which precede his birth—the birthplace of his parents, for example—and minor incidents in his very early childhood—early homes, places of work etc within a small section of south London facilitate a compression of cinema history onto local historiography.

Chaplin is afforded the kind of geographical memorial frequently assigned to literary stars. The plotting of the coordinates of significant sites within his London life echoes the English Heritage plaques across the UK, which mark places of significance relating to influential figures from national history (such a plaque has been erected in Chaplin’s memory on the outer wall of his childhood home in Methely Street, Kennington).

The map’s function within the exhibit as a whole can be seen as a way of nationalizing Chaplin and reclaiming his silent screen Tramp persona from American cinema history. While later sections of the gallery space give way to charting Chaplin’s dominance of Hollywood (see, for example, the Chaplin-on-set display with the prominent ‘Hollywood’ sign featured in the background), the map attempts to ground the star within the familiar and the local, making Chaplin a British star rather than a Hollywood star, and specifically a London star.

2. Art Dept. Living exhibition / performed archive

A small amount of gallery space is given over to the ‘Art Department’—a space of semi-exhibition in which film artifacts are displayed alongside a handful of working artists, who are present daily sketching and designing at story-boarding stations.

The display of the living production of film projects offers the museum visitor a glimpse into the strange duality of a process which both produces future film texts and creates as a byproduct of this production ephemeral artifacts which, depending on the success and cultural impact of their overarching film project, will potentially become archived objects worthy of entering the surrounding displays within the museum.

At the same time, the staged nature of the ‘exhibit’ implies a notion of the archive as performance. Here we witness an archive being continuously created as a spectatorial process. The performed activities of the creative film worker become an archived event in of itself.

The power to ultimately reclaim the byproducts of this kind of production—the sketches, drafts, plans and cast-offs that the workers are here creating in a continual flow—lies with the museum viewer as potential audience member. Their decision to consume the end product—the film—determines the validity of its creative by-products as cultural history. If the film these storyboarders are currently working on flops, their sketches will be archived as personal professional history; if the film makes a substantial cultural impact, measured by box office success, such materials will become ‘validated’ ephemeral cultural history…

3. Myths & Legends, Ray Harryhausen: elevating the animator to auteur

The Harryhausen exhibition takes the thrills and spills of classic blockbuster cinema and frames them with the reverence of the ‘official’ museum. Lowbrow film fodder is broken down into the sum of its creative parts in order to locate an auteur within a disparate group of action-adventure films.

By locating Harryhausen as the central artists upon which the success and validity of such film hinges, the exhibit discards narrative sophistication and critical validation in favour of endorsing the oeuvre of the special effects artist.

Models of monsters, sword wielding skeletons and snake-haired medusas are mounted, lit and encased within sleek glass display boxes.

A miniature of Harryhausen’s memorable medusa stop-motion model is mounted in a dimly lit room, beside a huge screen projecting the Medusa scene from the original Clash of the Titans on a loop. Museum visitors enter this room in a reverential silence enforced by the darkness and glorifying single point of light illuminating the tiny stop-motion model.

In the following room, Harryhausen is rendered in a life-size bronze statue, depicted as the powerful creator of movie magic holding a miniature skeleton from Jason and the Argenauts in his outstretched hand.

The display seeks ultimately to elevate Harryhausen’s work to auteur status in this way, further underscoring his significance by situating his work within a plotted history of stop-motion rooted in the pre-cinematic experimentation of Eadweard Muybridge.

Combining a reputable lineage of scientific advancement in visual experimentation with the trappings of the ‘official’ museum display and the prestige of cultural heritage this lends, the exhibition elevates the profile of Harryhausen’s work by divorcing his ‘artistry’ from its containing ‘entertainment’ textual forms. The Medusa creation in particular is thereby free to be celebrated as a technical achievement—one which surpasses the lowbrow connotations of the film in which it features.

Text by Lisa Stead, PhD Candidate, Dept. of English, University of Exeter

Labels:

beyond text artefact,

case study,

London Film Museum

Thursday, 15 July 2010

Beyond Text: short research pieces, example 1

Co-organiser Jennifer and I will be adding short snippets of research as brief examples of the incorporation of beyond text material analysis into research. These short investigative and writing exercises aim to show how single objects can illuminate complicated research stories and histories, drawing upon our doctorial studies and experience working with these collections.

We strongly encourage participating Interfaces delegates, or any interested arts postgraduates to contribute to the blog by offering similar short reflection pieces on key ‘beyond texts’ objects which illuminate their own research… please email images and/or short clips supported by around 300 words of brief analysis to myself or Jennifer, (lrs204@ex.ac.uk / jab228@ex.ac.uk) discussing any such materials relevant to your own research interests.

We hope to get the ball rolling here with a few examples!

First up, Jen’s reflective piece on a BDC item…

Lisa

Packet of Olivier brand cigarettes: BDC Item No.: 74905

Type of Object: miscellaneous item

Material: paper

Language: English

Country of Origin: UK

Manufacturer: Benson & Hedges Ltd., London

In the early 1950s Laurence Olivier’s star image is marked by a tension between two different and apparently irreconcilable understandings of what constitutes British celebrity during the post-war period, a tension that is, in turn, indicative of wider relations between the post-war British and American film industries. Specifically, Olivier is imagined as oscillating between two different modes of stardom: the theatrical and the cinematic. Here, the former is defined as representative of the prestige and heritage of the nation while the latter suggests a Hollywood-influenced commodification of the star image that is seen as incompatible with theatrical (and explicitly British) star discourses.

This packet of Olivier cigarettes (a brand initiated in 1956 after the success of Richard III) enables me to focus and clarify my research by outlining my argument in relation to a contemporary object that directly cites the tensions that I am exploring. The cigarettes are themselves indelibly marked by the conflict that characterises Olivier’s star image in the early 1950s. Representing a saleable commodity that trades on the Olivier name, the cigarette packaging also evokes the national prestige associated with their namesake. Thus, the white and blue suggests the colours of the Royal Navy uniform that Olivier himself had worn during the war, while the golden imprint of the coat of arms explicitly asserts Olivier’s connection to the nation and its heritage as a cipher for “Shakespeare” and knight of the realm. Advertisements for the cigarettes cite key words associated with Olivier’s star image: “cool”, “smooth”, “elegant”, “quality”; but the Hollywood-style commodification that the cigarettes ultimately suggest is imagined as incompatible with Olivier’s status as a national icon. An outraged Lieutenant Colonel CJ Barton-Innes of Kensington wrote to Olivier in 1956, declaring that it is “inconceivable that one who had received the honour of a knighthood from his sovereign could so besmirch the dignity conferred upon him as to sell his name for such an ignominious purpose as to boost a brand of cigarettes”.

We strongly encourage participating Interfaces delegates, or any interested arts postgraduates to contribute to the blog by offering similar short reflection pieces on key ‘beyond texts’ objects which illuminate their own research… please email images and/or short clips supported by around 300 words of brief analysis to myself or Jennifer, (lrs204@ex.ac.uk / jab228@ex.ac.uk) discussing any such materials relevant to your own research interests.

We hope to get the ball rolling here with a few examples!

First up, Jen’s reflective piece on a BDC item…

Lisa

Smoke Signals: 'Olivier Cigarettes' and the marketing of a post-war British star

Packet of Olivier brand cigarettes: BDC Item No.: 74905

Type of Object: miscellaneous item

Material: paper

Language: English

Country of Origin: UK

Manufacturer: Benson & Hedges Ltd., London

In the early 1950s Laurence Olivier’s star image is marked by a tension between two different and apparently irreconcilable understandings of what constitutes British celebrity during the post-war period, a tension that is, in turn, indicative of wider relations between the post-war British and American film industries. Specifically, Olivier is imagined as oscillating between two different modes of stardom: the theatrical and the cinematic. Here, the former is defined as representative of the prestige and heritage of the nation while the latter suggests a Hollywood-influenced commodification of the star image that is seen as incompatible with theatrical (and explicitly British) star discourses.

This packet of Olivier cigarettes (a brand initiated in 1956 after the success of Richard III) enables me to focus and clarify my research by outlining my argument in relation to a contemporary object that directly cites the tensions that I am exploring. The cigarettes are themselves indelibly marked by the conflict that characterises Olivier’s star image in the early 1950s. Representing a saleable commodity that trades on the Olivier name, the cigarette packaging also evokes the national prestige associated with their namesake. Thus, the white and blue suggests the colours of the Royal Navy uniform that Olivier himself had worn during the war, while the golden imprint of the coat of arms explicitly asserts Olivier’s connection to the nation and its heritage as a cipher for “Shakespeare” and knight of the realm. Advertisements for the cigarettes cite key words associated with Olivier’s star image: “cool”, “smooth”, “elegant”, “quality”; but the Hollywood-style commodification that the cigarettes ultimately suggest is imagined as incompatible with Olivier’s status as a national icon. An outraged Lieutenant Colonel CJ Barton-Innes of Kensington wrote to Olivier in 1956, declaring that it is “inconceivable that one who had received the honour of a knighthood from his sovereign could so besmirch the dignity conferred upon him as to sell his name for such an ignominious purpose as to boost a brand of cigarettes”.

Text by Jennifer Barnes, PhD Candidate, University of Exeter, Dept. of English. July 2010.

Labels:

BDC,

beyond text artefact,

ephemera,

marketing,

nationality,

stars

Monday, 12 July 2010

Beyond Text: Bill Douglas Centre artefacts, part 1

The Interfaces event will feature a special workshop session in Exeter's Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture.

To support the event, we will be featuring on the blog some examples of 'beyond text' treasures available for viewing and research in the archive and museum.

First up: optical toys...

The video below shows the peep-show view of the centre's functioning mutoscope, followed by a few close up shots of one of the centre's replica zeotropes (shot rather shoddily on my phone camera--higher quality images will follow!)

For further interactive videos of zeotrope animation, visit the BDC site, linked here:

http://billdouglas.ex.ac.uk/eve/di/69110.htm

More coming soon....

Lisa

To support the event, we will be featuring on the blog some examples of 'beyond text' treasures available for viewing and research in the archive and museum.

First up: optical toys...

The video below shows the peep-show view of the centre's functioning mutoscope, followed by a few close up shots of one of the centre's replica zeotropes (shot rather shoddily on my phone camera--higher quality images will follow!)

For further interactive videos of zeotrope animation, visit the BDC site, linked here:

http://billdouglas.ex.ac.uk/eve/di/69110.htm

More coming soon....

Lisa

Labels:

BDC,

moving images,

optical toys,

pre-cinema,

video

Sunday, 11 July 2010

CALL FOR PAPERS NOW ACTIVE!

Interfaces: encounters beyond the page / screen / stage

1 Day Postgraduate Research Workshop Event, 29th January 2011

Confirmed Keynote Speaker: Dr Judith Buchanan (University of York)

This innovative multidisciplinary research training event examines questions of mediation and memory in encounters with non-textual archival materials in the arts. By creating dialogues between postgraduates and experienced researchers, and featuring practical sessions with curators and archivists, the research workshop seeks to investigate issues that take the researcher beyond the text in the investigation of objects and artefacts that constitute non-textual interfaces between film, literature and theatre.

Participating speakers and delegates will attend a central workshop event in the University’s Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture and Exeter’s Special Collections, where a hands-on exploration of key filmic and literary non-textual materials will be led by the curators of these archives.

Abstract for 20 minute papers are welcomed on the following core panel themes from postgraduates across the arts disciplines in drama, literature, film and modern languages:

• Performativity: transitory forms created by performance and performativity; improvisation and the play script; the body in play; performance and photographs/stills; the critical interpretation of ephemera; the incorporation of non-print ephemera into academic scholarship; mediations between public interest and critical histories surrounding popular artefacts; the function of stage props

• Beyond ‘Adaptation’: mediations involved in processes of adaptation across disciplines / media; the creation and sustenance of ‘media memories’ in repeated adaptation

• Forms of Engagement: creative forms which overlap across the arts—such as illustrations, sound recordings, and poetic readings; the translation and migration of theatrical, literary and filmic heritages into business practices; non-narrative auto/biographical sites

• Production History: the exploration of how plays have been ‘framed’ in discussion, presentation and analysis across their history; exploring the relationship between "text" and "performance"

• Digital Cultures: the impact of digitization upon the archival ‘text’; the impact of new digital media upon process of memory / memorial; multimedia practices and presentations

• Rethinking archives: how archives destabilize notions of ‘text’ / the search for archival authorial ‘presence’; archival silences; notions of the archive as performance; questions of authority surrounding pre-texts / printed texts; challenges encountered in recreating draft manuscripts; the impact of ‘anecdotal’ archival material

We strongly encourage speakers to present the ‘beyond text’ materials of their research in a multi-media format, bringing evidence of cornerstone non-textual examples—sound clip / manuscript image / artwork etc.

Please submit 300 word abstracts for 20 minute papers to Lisa Stead (lrs204@ex.ac.uk) and Jennifer Barnes (jab228@ex.ac.uk). Suggestions for panels of 3 speakers for any of the given core panel themes are also welcomed. Deadline: October 1st, 2010.

1 Day Postgraduate Research Workshop Event, 29th January 2011

Confirmed Keynote Speaker: Dr Judith Buchanan (University of York)

This innovative multidisciplinary research training event examines questions of mediation and memory in encounters with non-textual archival materials in the arts. By creating dialogues between postgraduates and experienced researchers, and featuring practical sessions with curators and archivists, the research workshop seeks to investigate issues that take the researcher beyond the text in the investigation of objects and artefacts that constitute non-textual interfaces between film, literature and theatre.

Participating speakers and delegates will attend a central workshop event in the University’s Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture and Exeter’s Special Collections, where a hands-on exploration of key filmic and literary non-textual materials will be led by the curators of these archives.

Abstract for 20 minute papers are welcomed on the following core panel themes from postgraduates across the arts disciplines in drama, literature, film and modern languages:

• Performativity: transitory forms created by performance and performativity; improvisation and the play script; the body in play; performance and photographs/stills; the critical interpretation of ephemera; the incorporation of non-print ephemera into academic scholarship; mediations between public interest and critical histories surrounding popular artefacts; the function of stage props

• Beyond ‘Adaptation’: mediations involved in processes of adaptation across disciplines / media; the creation and sustenance of ‘media memories’ in repeated adaptation

• Forms of Engagement: creative forms which overlap across the arts—such as illustrations, sound recordings, and poetic readings; the translation and migration of theatrical, literary and filmic heritages into business practices; non-narrative auto/biographical sites

• Production History: the exploration of how plays have been ‘framed’ in discussion, presentation and analysis across their history; exploring the relationship between "text" and "performance"

• Digital Cultures: the impact of digitization upon the archival ‘text’; the impact of new digital media upon process of memory / memorial; multimedia practices and presentations

• Rethinking archives: how archives destabilize notions of ‘text’ / the search for archival authorial ‘presence’; archival silences; notions of the archive as performance; questions of authority surrounding pre-texts / printed texts; challenges encountered in recreating draft manuscripts; the impact of ‘anecdotal’ archival material

We strongly encourage speakers to present the ‘beyond text’ materials of their research in a multi-media format, bringing evidence of cornerstone non-textual examples—sound clip / manuscript image / artwork etc.

Please submit 300 word abstracts for 20 minute papers to Lisa Stead (lrs204@ex.ac.uk) and Jennifer Barnes (jab228@ex.ac.uk). Suggestions for panels of 3 speakers for any of the given core panel themes are also welcomed. Deadline: October 1st, 2010.

Welcome to Interfaces

Welcome to the supporting blog for the forthcoming Interfaces: encounters beyond the page / screen / stage workshop and exhibition. This blog will feature a variety of materials across the life of the event and beyond. We will be featuring video, photography and podcast recordings from the workshop in January, and materials from the supporting exhibition.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)