Case Study: Beyond Text encounters at the Movieum London Film Museum

New to the London Film Museum for 2010 is an exhibition celebrating the work of stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, entitled “Myths & Legends”. The exhibit--which displays a huge variety of miniatures, prototypes, and models from classic special effects movies such as Clash of the Titans and Jason and the Argonauts—constitutes an illuminating addition to a museum which focuses strongly upon ‘beyond text’ materials in the preservation and interpretation of cinema history and its impact upon popular culture.

The museum presents several distinct collections of materials, each crafted in distinct ways around approaches to cinema as cultural practice, industrial history, social history, creative industry and national identity.

My intention here is to touch briefly upon a few of the museum highlights as examples of interpretative beyond text practices which engage notions of mediation and memory at the interface between critical analysis, archival preservation and public consumption

1. Chaplin Exhibition: the interactive map and the local reclamation of a global icon

The film museum features an extensive exhibit dedicated solely to charting the career and personal life of global comedy superstar Charlie Chaplin. What is interesting in the museum’s presentation of Chaplin is its attempts reclaim Chaplin as an explicitly national –and further a local cultural icon.

By offsetting a vast collection of ephemera surrounding and constructing his star image across a huge span of film history against a highly detailed account of his pre-cinema personal life and early career in Britain, the museum is careful to assert that Chaplin’s work and life outside of England is as an ‘exhile’.

One particular non-textual example from the exhibition illustrates this. The interactive map display is a wall panel with a street map view of a section of south London featuring a series of small red LED’s. These are able to be lit up by the museum visitor by pressing buttons beside a list of headings, which explain the plotting of each light as a site significant within Chaplin’s early life.

The detailed attention to incidents in Chaplin’s family life which precede his birth—the birthplace of his parents, for example—and minor incidents in his very early childhood—early homes, places of work etc within a small section of south London facilitate a compression of cinema history onto local historiography.

Chaplin is afforded the kind of geographical memorial frequently assigned to literary stars. The plotting of the coordinates of significant sites within his London life echoes the English Heritage plaques across the UK, which mark places of significance relating to influential figures from national history (such a plaque has been erected in Chaplin’s memory on the outer wall of his childhood home in Methely Street, Kennington).

The map’s function within the exhibit as a whole can be seen as a way of nationalizing Chaplin and reclaiming his silent screen Tramp persona from American cinema history. While later sections of the gallery space give way to charting Chaplin’s dominance of Hollywood (see, for example, the Chaplin-on-set display with the prominent ‘Hollywood’ sign featured in the background), the map attempts to ground the star within the familiar and the local, making Chaplin a British star rather than a Hollywood star, and specifically a London star.

2. Art Dept. Living exhibition / performed archive

2. Art Dept. Living exhibition / performed archive

A small amount of gallery space is given over to the ‘Art Department’—a space of semi-exhibition in which film artifacts are displayed alongside a handful of working artists, who are present daily sketching and designing at story-boarding stations.

The display of the living production of film projects offers the museum visitor a glimpse into the strange duality of a process which both produces future film texts and creates as a byproduct of this production ephemeral artifacts which, depending on the success and cultural impact of their overarching film project, will potentially become archived objects worthy of entering the surrounding displays within the museum.

At the same time, the staged nature of the ‘exhibit’ implies a notion of the archive as performance. Here we witness an archive being continuously created as a spectatorial process. The performed activities of the creative film worker become an archived event in of itself.

The power to ultimately reclaim the byproducts of this kind of production—the sketches, drafts, plans and cast-offs that the workers are here creating in a continual flow—lies with the museum viewer as potential audience member. Their decision to consume the end product—the film—determines the validity of its creative by-products as cultural history. If the film these storyboarders are currently working on flops, their sketches will be archived as personal professional history; if the film makes a substantial cultural impact, measured by box office success, such materials will become ‘validated’ ephemeral cultural history…

3. Myths & Legends, Ray Harryhausen: elevating the animator to auteur

The Harryhausen exhibition takes the thrills and spills of classic blockbuster cinema and frames them with the reverence of the ‘official’ museum. Lowbrow film fodder is broken down into the sum of its creative parts in order to locate an auteur within a disparate group of action-adventure films.

By locating Harryhausen as the central artists upon which the success and validity of such film hinges, the exhibit discards narrative sophistication and critical validation in favour of endorsing the oeuvre of the special effects artist.

Models of monsters, sword wielding skeletons and snake-haired medusas are mounted, lit and encased within sleek glass display boxes.

A miniature of Harryhausen’s memorable medusa stop-motion model is mounted in a dimly lit room, beside a huge screen projecting the Medusa scene from the original Clash of the Titans on a loop. Museum visitors enter this room in a reverential silence enforced by the darkness and glorifying single point of light illuminating the tiny stop-motion model.

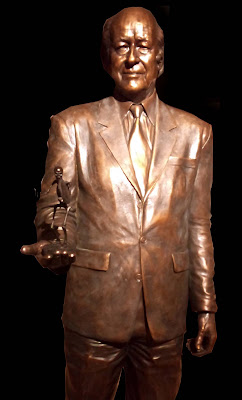

In the following room, Harryhausen is rendered in a life-size bronze statue, depicted as the powerful creator of movie magic holding a miniature skeleton from Jason and the Argenauts in his outstretched hand.

The display seeks ultimately to elevate Harryhausen’s work to auteur status in this way, further underscoring his significance by situating his work within a plotted history of stop-motion rooted in the pre-cinematic experimentation of Eadweard Muybridge.

Combining a reputable lineage of scientific advancement in visual experimentation with the trappings of the ‘official’ museum display and the prestige of cultural heritage this lends, the exhibition elevates the profile of Harryhausen’s work by divorcing his ‘artistry’ from its containing ‘entertainment’ textual forms. The Medusa creation in particular is thereby free to be celebrated as a technical achievement—one which surpasses the lowbrow connotations of the film in which it features.